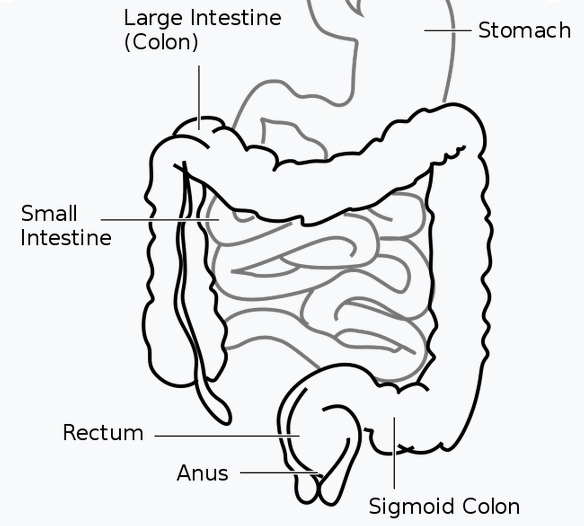

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the digestive tract. It can cause inflammation in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus, but most commonly affects the ileum (the last part of the small intestine) and the colon (the large intestine).

History:

The concept of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) was first described by Giovanni Battista Morgagni in the 18th century. He was an Italian anatomist and physician who is considered the father of modern pathological anatomy. He described cases of inflammatory changes in the intestinal tract in his book “The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy”.

However, it wasn’t until the 20th century that the term “inflammatory bowel disease” (IBD) was coined and the two distinct forms of IBD, Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s disease were differentiated. In 1913, Scottish physician T Kennedy Dalziel published a paper in which he described a condition that he called “regional ileitis,” which is now considered to be a form of Crohn’s disease.

The term “Crohn’s disease” is named after Dr. Burrill B. Crohn, who first described the condition in a paper published in 1932. Dr. Crohn was a physician at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City and he, along with his colleagues Dr. Leon Ginzburg and Dr. Gordon D. Oppenheimer, published a paper in the journal “The Journal of the American Medical Association” describing a new disease characterized by inflammation of the ileum (the last part of the small intestine) and colon (the large intestine).

They named the condition “regional ileitis,” but it later became known as “Crohn’s disease” in honor of Dr. Crohn, who was the lead author on the paper. Dr. Crohn and his colleagues recognized that this condition was different from other forms of inflammatory bowel disease, such as ulcerative colitis, which affects only the colon and rectum, and it was the first time this type of disease was described in medical literature.

Symptoms:

Crohn’s disease can cause a wide range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea (which may be bloody if inflammation is severe), fever, abdominal distension (swelling or bloating), and weight loss. Other common symptoms include fatigue, loss of appetite, and malnutrition. Some people with Crohn’s disease may also experience extraintestinal symptoms, such as joint pain, skin rashes, and eye inflammation. The symptoms of Crohn’s disease can vary widely from person to person and may change over time, often fluctuating between periods of remission (when symptoms are mild or absent) and flare-ups (when symptoms are more severe).

Diagnosis:

Crohn’s disease can be difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and ulcerative colitis. A number of tests are typically used to help diagnose Crohn’s disease and rule out other conditions.

The following tests are commonly used in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease:

- Blood tests: Blood tests are done to check for anemia (a lack of red blood cells) and inflammation in the body. Blood tests can also check for a high white blood cell count, which is a sign of inflammation.

- Stool test: A stool test can be done to check for blood in the stool, which can be a sign of Crohn’s disease or other conditions.

- Imaging tests: Imaging tests such as a CT scan, MRI, or a small bowel follow-through (SBFT) can help to visualize the inside of the digestive tract and identify areas of inflammation, obstruction or fistulas.

- Endoscopy: Endoscopy is a procedure where a thin, flexible tube with a camera on the end is passed through the mouth or anus to examine the inside of the digestive tract. Upper endoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy are the most common used procedures.

- Biopsy: During an endoscopy, a small tissue sample can be taken and examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

- Capsule endoscopy: A capsule endoscopy is a test that uses a small camera in a capsule that is swallowed by the patient. The camera takes pictures of the inside of the small intestine and transmits the images to a recorder worn on the patient’s belt.

No single test can confirm the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, so doctors will typically use a combination of tests to make a diagnosis. Additionally, while the above tests can be used to diagnose Crohn’s disease, it is important to have a proper evaluation and diagnosis by a qualified healthcare professional.

A differential diagnosis is the process of identifying the most likely cause of a patient’s symptoms or condition, by considering all the possible diagnoses and then ruling out those that are less likely. It’s a way to narrow down the list of possible causes, based on the patient’s symptoms, medical history, examination, and test results. The final diagnosis is the one that best explains all of the patient’s symptoms and test results.

There are several other conditions that can present with symptoms similar to Crohn’s disease, including intestinal tuberculosis, Behçet’s disease, ulcerative colitis, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy (NSAID-induced enteropathy), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and celiac disease.

IBS can be excluded when there are inflammatory changes, as IBS is a functional disorder and does not involve inflammation. Celiac disease can also present with similar symptoms, but it can be distinguished from Crohn’s disease by the presence of specific antibodies (anti-transglutaminase antibodies) and the absence of intestinal villi atrophy. A proper evaluation and diagnosis by a qualified healthcare professional is crucial in determining the correct diagnosis and to come up with an appropriate treatment plan.

Crohn’s disease is typically diagnosed by a gastroenterologist, a doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of conditions that affect the digestive system.

A gastroenterologist will take a thorough medical history and perform a physical examination. They may also order a series of tests and procedures such as blood tests, stool tests, imaging tests, endoscopy, and biopsy. They may also refer the patient to other specialists such as a radiologist or a pathologist to interpret test results.

Antibodies:

There are no specific antibodies that are exclusively associated with Crohn’s disease, but some antibodies are more prevalent in people with Crohn’s disease than in the general population. These include:

- Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA): These antibodies are found in a small percentage of people with Crohn’s disease, and are more commonly associated with another form of inflammatory bowel disease called ulcerative colitis.

- ASCA (anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies): These antibodies are found in about 50-70% of people with Crohn’s disease, particularly those with involvement of the small intestine.

- Anti-OmpC (Outer membrane protein C) antibodies: These antibodies are found in about 25-50% of people with Crohn’s disease, particularly those with involvement of the ileum (the last part of the small intestine).

- Anti-CBir1 (commensal bacteria-induced recruitment 1) antibodies: These antibodies are found in a small percentage of people with Crohn’s disease, and are associated with disease in the colon.

The presence of these antibodies does not confirm a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, and a positive test result should be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation and other test results. A proper evaluation and diagnosis by a qualified healthcare professional is needed in determining the correct diagnosis.

It is possible to test for these antibodies in the blood, and it can be done in specialized laboratory or clinical settings. But again, it’s important to keep in mind that these tests are not diagnostic per se, they are only one part of the diagnostic process and should be interpreted in the context of the patient’s symptoms, medical history, examination, and other test results.

There are several studies that have compared the different antibodies associated with Crohn’s disease. One such study is “Diagnostic accuracy of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan, anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1 antibodies in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis” by D. R. Probert, J. F. Colombel, and A. R. Hart published in the journal “Gut” in 2015.

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan (ASCA), anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1 antibodies for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The study included a meta-analysis of published studies that reported the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR) of these antibodies for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

The study found that the diagnostic accuracy of ASCA, anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1 antibodies is moderate to high, with the highest diagnostic accuracy seen for ASCA antibodies. They also found that the combination of ASCA and anti-OmpC antibodies had the highest diagnostic accuracy, with a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 89%.

Treatments:

Treatment for Crohn’s disease typically involves a combination of medications, lifestyle changes, and, in some cases, surgery. The goal of treatment is to reduce inflammation, alleviate symptoms, and improve the patient’s quality of life. The specific treatment plan will depend on the severity of the disease, the location and extent of inflammation, and the patient’s overall health.

Here are some of the treatments that are commonly used for Crohn’s disease:

- Medications:

- Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as mesalamine, sulfasalazine, and corticosteroids, can help to reduce inflammation and alleviate symptoms.

- Immunomodulators, such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, and adalimumab, can suppress the immune system and reduce inflammation.

- Biologic therapy, such as infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and vedolizumab, target specific parts of the immune system to reduce inflammation.

- Lifestyle changes:

- Eating a healthy diet, getting regular exercise, and quitting smoking can help to reduce inflammation and improve overall health.

- Stress management techniques, such as relaxation therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, can help to reduce stress and improve mental health.

- Surgery: Surgery may be necessary for complications of the disease such as strictures (narrowing of the intestine), fistulas (abnormal connections between organs or between an organ and the skin), or abscesses (collections of pus). Surgery may also be considered if the patient does not respond to medical treatment or if the disease is affecting the patient’s quality of life. Surgery options include removing the diseased part of the intestine (resection) or removing the entire colon (colectomy) with or without formation of an ileoanal pouch.

Support Groups:

There are several national and international support groups for people with Crohn’s disease. Some of the more well-known support groups include:

- Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation: This is a non-profit organization that provides support and resources for people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. They offer a wide range of services, including support groups, educational programs, and research funding.

- Take Control of Crohn’s: This is an online community that provides support and resources for people with Crohn’s disease and their loved ones. They offer online support groups, a forum for discussing treatment options, and a directory of local support groups.

- International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD): This is a global organization that provides support and resources for people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease. They offer a directory of local support groups and an online forum for discussing treatment options.

- IBD Patient Support: This is an online community that provides support and resources for people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease. They offer online support groups, a forum for discussing treatment options, and a directory of local support groups.

- Crohn’s & Colitis UK: This is a UK-based charity that provides support and resources for people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. They offer support groups, educational programs, and research funding.

Books Sources:

- Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: The Essential Guide” by Professor John Hunter, Andrew Bateman, and Dr. Rachel Burch. Published by Oxford University Press, 2018.

- “The First Year: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis” by Jill Sklar and Hillary Steinhart. Published by Marlowe & Company, 2002.

- “The Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Diet Book” by Dr. Joel Fuhrman. Published by St. Martin’s Press, 2018

- “Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: The Complete Guide” by Dr. David S. T. Goldstein. Published by Oxford University Press, 2020.

Research Published on Crohn’s:

- “The gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: current knowledge and future directions” by J. Mark Sutton and Simon M. Murch. Published in the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2020. The authors review the current understanding of the role of gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of IBD and the potential therapeutic targets and strategies.

- “A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vedolizumab in moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease” by William J. Sandborn et al. Published in The New England Journal of Medicine, 2013. This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of the drug vedolizumab, an anti-integrin therapy, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease and found that it was effective in inducing and maintaining remission.

- “The role of nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease” by Emma G. M. Heuschkel and Paul W. J. Peters. Published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 2018. The authors review the evidence for the role of nutrition in the management of pediatric IBD, including enteral and parenteral nutrition and the effects of dietary interventions.

- “Infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease” by David T. Rubin et al. Published in The Lancet, 1999. This study shows that infliximab, a biological therapy, is effective in inducing and maintaining remission in Crohn’s disease, especially in patients who have not responded to conventional therapy.