Introduction

In the vast world of nutrition, nitrates and nitrites play a unique and sometimes misunderstood role. Their presence in food has spurred both health concerns and revelations about potential benefits. Let’s delve into understanding these compounds and their significance in our diet.

What are Nitrates and Nitrites?

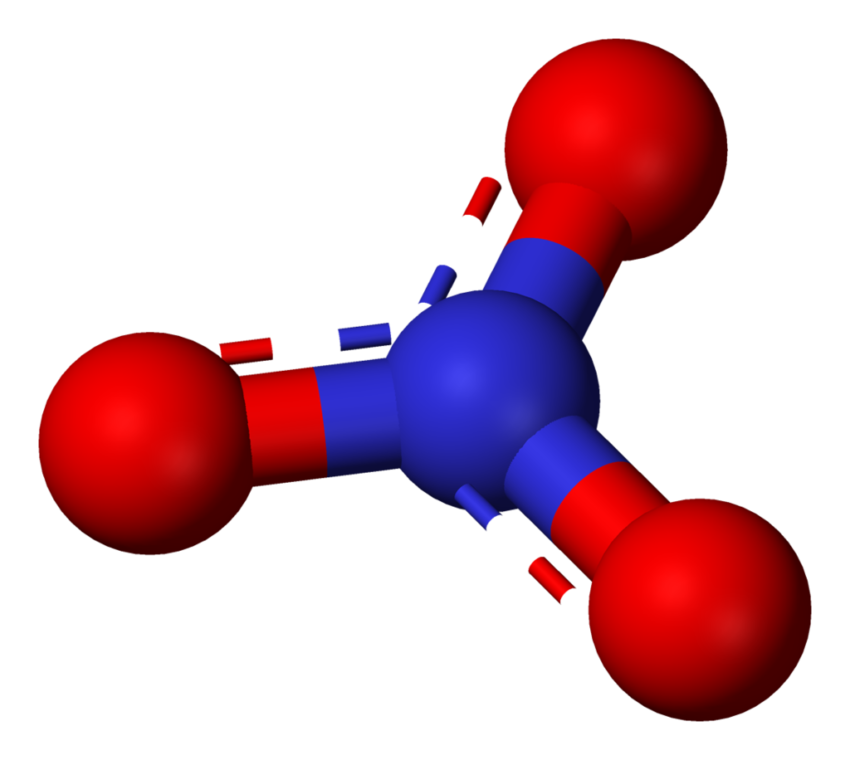

Nitrates (NO3-) and nitrites (NO2-) are naturally occurring inorganic ions that are part of the nitrogen cycle. Nitrates are a stable form of nitrogen found abundantly in our environment, particularly in the soil, where they are used by plants as a critical nutrient. When we consume plants, we indirectly take in these nitrates.

Nitrites, on the other hand, are a less stable, reduced form of nitrates. They are produced inside our bodies from nitrates through a process called nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway. This conversion also takes place in certain conditions in the environment and during the curing process of some meats.

The Importance of Nitrates and Nitrites for Health

Nitrates and nitrites have been found to play crucial roles in human health, primarily due to their conversion to nitric oxide (NO) within the body4. Nitric oxide is a vital signaling molecule with various functions in the body, including regulation of blood pressure, immune response, and brain function.

Role in Blood Pressure Regulation

Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator, meaning it helps to relax and widen blood vessels. This function can aid in reducing blood pressure, thus improving overall cardiovascular health.

Immune Response and Pathogen Defense

NO has been shown to be an essential part of the body’s defense system, possessing antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens.

Brain Function

Nitric oxide is involved in neurotransmission and has been associated with memory and behavior functions. It has a role in the modulation of neuroplasticity and in neuroprotection.

Vegetables: A Prime Source of Dietary Nitrates

Vegetables are a rich dietary source of nitrates. Leafy green vegetables and root vegetables, such as arugula, rhubarb, celery, and beetroot, typically contain the highest amounts. Consuming a diet rich in a variety of vegetables not only provides a range of nutritional benefits but also contributes to the body’s nitrate intake, potentially offering the health advantages associated with nitric oxide production.

In the sections to follow, we will explore the nitrate content of various vegetables, discuss the impact of cooking methods on nitrate levels, and address some of the common misconceptions surrounding dietary nitrates.

List of Good Sources of Nitrates

Please note that actual nitrate content can vary significantly based on the soil the vegetable was grown in, its maturity, and other factors. The percentages are relative to arugula.

Here is a rough estimate for comparison:

- Arugula: (Top Source)

- Rhubarb: 90% (relative to Arugula)

- Celery: 85%

- Beetroot: 80%

- Spinach: 75%

- Lettuce (especially butter leaf and iceberg): 70%

- Swiss chard: 65%

- Bok choy: 60%

- Radishes: 55%

- Turnip greens: 50%

- Chinese cabbage: 45%

- Collard greens: 40%

- Cilantro: 35%

- Mustard greens: 35%

- Endive: 30%

- Kale: 25%

- Carrots: 20%

- Leek: 15%

- Green beans: 10%

- Red bell peppers: 5%

These estimates are very rough. Consuming a diet rich in a variety of vegetables is likely to provide a broad range of nutritional benefits, including but not limited to nitrate intake.

Nitrate Content in Vegetables: From Arugula to Red Bell Peppers

As we’ve established, vegetables are a significant source of dietary nitrates. Some vegetables contain higher amounts than others. Arugula often tops the list for its impressive nitrate content, followed by others like rhubarb, celery, and beetroot. Even vegetables with lesser amounts, such as red bell peppers, contribute to our overall nitrate intake.

The nitrate content in vegetables can vary depending on several factors such as the soil they’re grown in, their maturity, and other environmental conditions. However, their overall contribution to dietary nitrates remains consistent.

How Cooking Methods Impact Nitrate Levels

Different cooking methods can affect the nitrate content of vegetables. Boiling, for instance, can lead to a significant loss of nitrates as they are soluble and can leach into the cooking water. Steaming or microwaving vegetables may retain more nitrates. Raw consumption often yields the highest nitrate content, making salads an excellent way to maximize nitrate intake.

Addressing the Nitrate-Nitrite Controversy

While the health benefits of dietary nitrates from vegetables are clear, there has been controversy surrounding nitrates and nitrites in cured meats and their potential link to health issues, including cancer.

It’s essential to note that the difference lies in the source and context of nitrate and nitrite intake. In processed meats, nitrites are used as preservatives and may interact with other components, leading to the formation of potentially harmful substances, like N-nitroso compounds.

On the other hand, vegetable-derived nitrates are accompanied by a host of other beneficial compounds, including antioxidants, which may help prevent the formation of harmful substances in the body. Thus, focusing on a diet rich in a variety of vegetables remains a sound nutritional strategy.

Understanding nitrates and nitrites, their roles, sources, and effects on health, can guide us to make healthier dietary choices. Incorporating nitrate-rich vegetables in our diets is one such choice, contributing to our overall well-being.

Cardiovascular Benefits

Nitrates from vegetables can contribute to cardiovascular health in several important ways, largely due to their conversion into nitric oxide (NO) in the body.

Vasodilation and Blood Pressure Regulation

Firstly, nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator. This means it helps to relax and expand blood vessels, allowing blood to flow more freely. This function can help lower blood pressure, which is one of the key risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Regular consumption of nitrate-rich vegetables can lead to an increase in the body’s nitric oxide production, thus promoting better blood pressure control. Studies have shown that a diet high in these vegetables can reduce blood pressure, especially in people with hypertension.

Protection Against Atherosclerosis

Nitric oxide can also help prevent the development of atherosclerosis, a condition characterized by the hardening and narrowing of the arteries. Atherosclerosis is a major underlying cause of heart attacks and strokes.

Nitric oxide can prevent atherosclerosis by inhibiting the adhesion and aggregation of platelets and white blood cells, which are early steps in the development of arterial plaque. It also reduces the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, a key factor in plaque buildup.

Enhanced Exercise Performance

Furthermore, dietary nitrates can enhance physical performance, particularly in endurance exercises. They improve the efficiency of the mitochondria, the energy-producing structures in cells, and reduce the oxygen cost of exercise6. These benefits can lead to improved cardiovascular fitness and overall heart health.

By including nitrate-rich vegetables in your diet, you can support your cardiovascular health in these significant ways.

Diabetes

The role of dietary nitrates from vegetables in the management of diabetes is an area of ongoing research. Here are some of the potential ways dietary nitrates might benefit individuals with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes:

Improved Insulin Sensitivity

There’s evidence suggesting that nitric oxide (NO) can improve insulin sensitivity. Insulin sensitivity refers to how responsive the body’s cells are to insulin. When cells are more sensitive, less insulin is needed to move glucose into cells. Poor insulin sensitivity (insulin resistance) is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes.

Vascular Health

People with diabetes are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease. As mentioned earlier, dietary nitrates can be converted into nitric oxide in the body, which helps maintain vascular health by regulating blood pressure, preventing clotting and controlling plaque buildup in the arteries. These effects can lower the risk of cardiovascular complications in individuals with diabetes.

Reduced Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress, a state of imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants, is often elevated in people with diabetes and contributes to the progression of the disease and its complications. Dietary nitrates may help reduce oxidative stress by promoting the production of nitric oxide, which exhibits antioxidant properties.

Improved Exercise Performance

For people with diabetes, regular physical activity is a key part of managing blood glucose levels. Dietary nitrates have been shown to enhance exercise performance, which could help individuals with diabetes maintain a consistent exercise routine.

Remember that while nitrate-rich vegetables can be a beneficial part of a diet for individuals with diabetes, they are not a replacement for a comprehensive diabetes management plan. This plan should also include regular physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, medication if prescribed, and other dietary considerations.

Other Health Conditions

In conclusion, the consumption of nitrate-rich vegetables has been linked to a variety of health benefits, not only for cardiovascular health and diabetes management, but also for several other conditions:

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Nitric oxide, derived from dietary nitrates, plays a role in neuroprotection. It’s involved in neurotransmission and has been associated with memory and behavior functions. Therefore, nitrate-rich diets may have potential benefits in the context of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Gastrointestinal Health

Nitrate intake could help maintain a healthy gastrointestinal tract. Nitric oxide, produced from dietary nitrates, helps regulate the motility of the digestive system, and also possesses antimicrobial activity that could influence gut health.

Respiratory Health

In the context of respiratory health, dietary nitrates may improve oxygenation in conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This is because nitric oxide helps to dilate the bronchi and bronchioles in the lungs, facilitating easier breathing.

Physical Performance

In the realm of physical fitness, dietary nitrates have been shown to improve the efficiency of oxygen usage during exercise, enhance muscle contraction and reduce fatigue.

While these potential benefits of dietary nitrates are promising, it’s essential to remember that a balanced and varied diet, regular exercise, and a healthy lifestyle are key to disease prevention and health promotion. Consuming a diet rich in nitrate-dense vegetables is just one part of this bigger picture.

References:

- Gruber, N., & Galloway, J. N. (2008). An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature, 451(7176), 293-296.

- Hord, N. G., Tang, Y., & Bryan, N. S. (2009). Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 90(1), 1-10.

- Lundberg, J. O., Weitzberg, E., & Gladwin, M. T. (2008). The nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nature reviews Drug discovery, 7(2), 156-167.

- Bryan, N. S., & Loscalzo, J. (2017). Nitrite and Nitrate in Human Health and Disease. Humana Press.

- Santamaria, P. (2006). Nitrate in vegetables: toxicity, content, intake and EC regulation. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 86(1), 10-17.

- Tamburrino, A., & Vitale, S. (2019). Nitrate in vegetables: a review on its occurrence and human health effects. European Food Research and Technology, 245(9), 1839-1851.

- Pannala, A. S., Mani, A. R., Spencer, J. P., & Skinner, V. (2002). The effect of dietary nitrate on salivary, plasma, and urinary nitrate metabolism in humans. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 34(5), 576-584.

- Bryan, N. S., Alexander, D. D., Coughlin, J. R., Milkowski, A. L., & Boffetta, P. (2012). Ingested nitrate and nitrite and stomach cancer risk: an updated review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 50(10), 3646-3665.

- IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat. (2015). IARC.

- Song, P., Wu, L., & Guan, W. (2015). Dietary nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines intake and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis

- Hord, N. G., Tang, Y., & Bryan, N. S. (2009). Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 90(1), 1-10.

- Cosby, K., Partovi, K. S., Crawford, J. H., Patel, R. P., Reiter, C. D., Martyr, S., … & Lancaster Jr, J. R. (2003). Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nature medicine, 9(12), 1498-1505.

- Webb, A. J., Patel, N., Loukogeorgakis, S., Okorie, M., Aboud, Z., Misra, S., … & MacAllister, R. (2008). Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension, 51(3), 784-790.

- Radomski, M. W., Palmer, R. M., & Moncada, S. (1987). The anti-aggregating properties of vascular endothelium: interactions between prostacyclin and nitric oxide. British journal of pharmacology, 92(3), 639-646.

- Beckman, J. S., Beckman, T. W., Chen, J., Marshall, P. A., & Freeman, B. A. (1990). Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 87(4), 1620-1624.

- Sansbury, B. E., & Hill, B. G. (2014). Regulation of obesity and insulin resistance by nitric oxide. Free radical biology and medicine, 73, 383-399.

- Hord, N. G., Tang, Y., & Bryan, N. S. (2009). Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 90(1), 1-10.

- Newsholme, P., Cruzat, V., Keane, K. N., Carlessi, R., & de Bittencourt, P. I. H. (2016). Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochemical Journal, 473(24), 4527-4550.

- Larsen, F. J., Weitzberg, E., Lundberg, J. O., & Ekblom, B. (2007). Dietary nitrate reduces maximal oxygen consumption while maintaining work performance in maximal exercise. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 46(2), 342-347.

- Calabrese, V., Mancuso, C., Calvani, M., Rizzarelli, E., Butterfield, D. A., & Stella, A. M. (2007). Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nature reviews Neuroscience, 8(10), 766-775.

- Lundberg, J. O., & Govoni, M. (2004). Inorganic nitrate is a possible source for systemic generation of nitric oxide. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 37(3), 395-400.

- Ricciardolo, F. L. (2003). Multiple roles of nitric oxide in the airways. Thorax, 58(2), 175-182.

- Jones, A. M. (2014). Dietary nitrate supplementation and exercise performance. Sports medicine, 44(1), 35-45.

Glossary of Terms

- Atherosclerosis: A condition that occurs when plaque builds up in the walls of the arteries, causing them to narrow and harden.

- Blood Pressure: The force that blood exerts against the walls of the arteries as it’s pumped through the body.

- Cardiovascular Disease: A class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels, including atherosclerosis, heart disease, and stroke.

- Dietary Nitrates: Compounds found naturally in some foods, especially green leafy vegetables and beetroot.

- Insulin Sensitivity: A measure of how responsive the body’s cells are to insulin. Increased insulin sensitivity means less insulin is needed to move glucose into cells.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Diseases characterized by the progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

- Nitric Oxide (NO): A gas produced naturally in the body that serves many functions, including acting as a vasodilator and neurotransmitter.

- Nitrates: A type of chemical compound that contains nitrogen and oxygen. They are found naturally in the soil and water, and in certain foods.

- Nitrites: Compounds that are formed when bacteria in the mouth and gut break down nitrates. Nitrites can be converted into nitric oxide in the body.

- Oxidative Stress: An imbalance between the production of free radicals and the body’s ability to counteract their harmful effects with antioxidants.

- Type 1 Diabetes: A chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin, a hormone needed to allow glucose to enter cells to produce energy.

- Type 2 Diabetes: A chronic condition that affects the way the body processes blood sugar (glucose). It’s characterized by insulin resistance, where the body’s cells are unable to respond properly to insulin.

- Vasodilation: The widening of blood vessels, which decreases blood pressure.

- Vascular Health: Refers to the health of the body’s network of blood vessels, including the arteries, veins, and capillaries.